#United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

HORRIFIC, DISTURBING VISIONS OF WAR INCOMING -- WAR IS A BLACK HOLE TO AVOID.

PIC INFO: Bomb bay camera in a TBF-1 Avenger from USS Essex captures the moment of bomb release over the Pasig River in downtown Manila, Luzon, Philippines, 14 Nov 1944. Attack was on the dock area 2,000 yards further ahead.

Photographer: Unknown.

Source: United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation.

Topic: Philippines Campaign, Phase 1, the Leyte Campaign.

Source: https://m.ww2db.com/image.php?image_id=24254 & Pinterest.

#War photography#War history#WWII#1944#War is Hell#Hell is War#Aerial Bombardment#The Philippines Campaign#TBF-1 Avenger#USS Essex#Pasig River Manila#Bombings#Aerial Bombing#World War II#World War 2#WW2#Forties#Pacific War#Philippines#40s#The Leyte Campaign 1944#Luzon Philippines#Luzon#Manila#Pacific Theater of War#1940s#The Philippines#Philippines Campaign WWII#United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

0 notes

Text

Chance Vought AU-1 Corsair de l'US Marine Corps – 1952

©United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation - 1986.145.002

#après-guerre#after war#corps des marines#us marine corps#aviation militaire#military aviation#avion de chasse#chasseur#fighter#chasseur-bombardier#fighter-bomber#chance vought f4u corsair#f4u corsair#corsair#au-1 corsair#1952

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vought OS2U Kingfisher taxiing after making a water landing near Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida.

Date: March 1943

United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation: link, link

#Vought OS2U Kingfisher#OS2U#Floatplane#Observation Plane#Seaplane#Spotter Plane#Aircraft#Airplane#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#WWII History#History#Military History#Naval Air Station Jacksonville#Jacksonville#Florida#March#1943#my post

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marine Air’s Dark Day at Midway

Marine Aircraft Group 22’s experience at the Battle of Midway serves as a hard lesson in trying to do too much with too little.

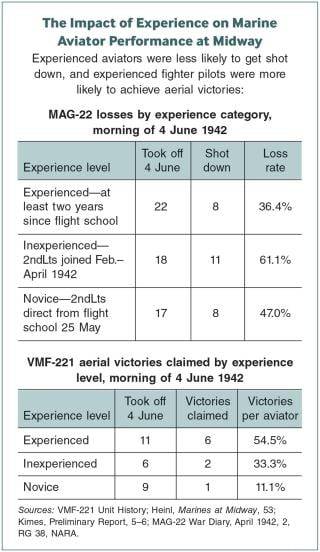

The 4th of June 1942 was a very bad day for Marine Corps aviation. At the Battle of Midway, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 suffered terrible losses and contributed little to the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s spectacular victory that day. The group’s fighting squadron, VMF-221, lost far more aircraft than its pilots shot down. Its dive-bomber squadron, VMSB-241, suffered staggering losses without hitting a single Japanese ship.

Midway historians have thoroughly chronicled the actions of these two squadrons and touched on some reasons for their performance. The most cited causes are the obsolescence of Marine aircraft and the inexperience of Marine aviators.1 A closer examination of archival material reveals additional factors that impaired the group’s performance at Midway and new insights into why MAG-22 sent such green pilots into battle.

The heart of MAG-22’s troubles lay in its two competing missions: While forward deployed to defend an advanced base, the group also served as a de facto training command for new aviators. This alone would have undermined its combat readiness. But additional factors worked against MAG-22. In the weeks before the battle, the flight hours the group devoted to training were limited by its responsibilities to defend Midway Atoll and by logistical shortfalls. During the battle, Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 were unable to coordinate aircraft from three services based at the atoll. Finally, imprecise direction from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz led to misunderstandings of how MAG-22 would employ its fighting squadron.

Present-day naval commanders are acutely familiar with the challenge of balancing combat readiness and forward presence. As naval leaders look for ways to maintain Navy and Marine Corps forces in the western Pacific and prepare for possible conflict there, the experience of MAG-22 at Midway provides a sobering reminder of the risks of attempting to do too much with too little.

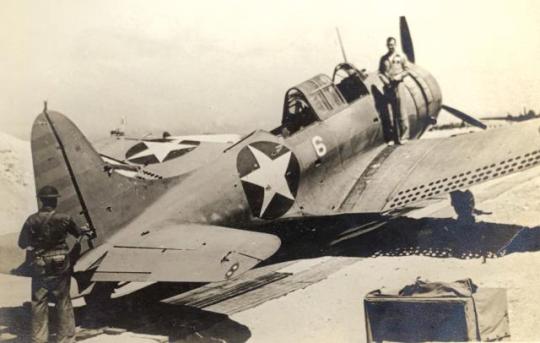

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. National Naval Aviation Museum

MAG-22’s Very Bad Day

At 0555 on 4 June 1942, Midway’s radar detected a large formation of aircraft 93 miles northwest of the atoll. MAG-22’s siren wailed. In accordance with orders issued the previous evening by Lieutenant Colonel Ira L. Kimes, the commander of MAG-22, VMF-221 launched its aircraft immediately. A detachment of six Navy TBF Avengers took off next, followed by four Army Air Forces B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The TBFs and B-26s proceeded independently to attack the Japanese carriers. The 16 SBD-2 Dauntlesses and 12 SB2U-3 Vindicators of VMSB-241 took off last and rendezvoused about 20 miles east of Midway’s Eastern Island.2

VMF-221’s commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks, had organized his 21 F2A-3 Buffalos and seven F4F-3 Wildcats into four divisions of Buffalos and one of Wildcats. All but one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 were mission ready and got airborne, though the divisions became slightly disorganized during the hasty scramble. The Japanese strike consisted of 108 aircraft—36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” carrier attack aircraft, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke,” or Zero, fighters. In accordance with Kimes’ plan, MAG-22’s fighter direction center funneled all five of VMF-221’s divisions to intercept the incoming strike. The Marines had the altitude advantage, and the separate divisions launched a series of overhead gunnery passes against the Japanese bomber formations. As the slower Marine aircraft recovered for additional passes, the nimbler Zeros overtook them and sent one after another tumbling downward.3

There is little doubt VMF-221 got the worst of the fight. The Japanese shot down 15 Marine fighters and severely damaged another nine, leaving just one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 ready to fly. Though Kimes afterward estimated Japanese losses at 43 aircraft, his surviving pilots definitively claimed just nine victories. Kimes’ estimate included “probable victories by missing fighter pilots” as well as claims by rear-seat gunners of VMSB-241.4 The actual total was far lower. VMF-221 probably shot down just three aircraft outright. Another 16 Japanese aircraft survived the raid but either ditched or were so irreparably damaged they could not fly again.5

A PBY Catalina flying boat had spotted the Japanese carriers, and MAG-22 passed their location to VMSB-241.6 Major Lofton R. Henderson, the squadron commander, led the SBDs. Major Benjamin W. Norris, the executive officer, led the SB2Us. While Henderson took his unit to 9,000 feet, Norris climbed to 13,000 feet.7 On paper, the SB2U-3s were nearly as fast as the SBD-2s, but the two flights proceeded independently.8

Because the Marine dive bombers were slower than the TBFs and B-26s, had taken off last, and had flown east before heading northwest, VMSB-241 did not attack until a half hour after the TBF and B-26 attacks had ended. The Japanese combat air patrol had shot down five of the six Avengers and two of the four Marauders; none had scored a hit. When Henderson and his SBDs spotted the carrier Hiryū at about 0755, the Japanese combat air patrol still had 13 fighters aloft.9

Henderson conducted a glide-bombing attack. A dive-bombing attack would have facilitated bombing accuracy and complicated fighter gunnery and antiaircraft solutions. But more than half of Henderson’s pilots were too inexperienced to attempt the technique, and the cloud cover would have made dive bombing particularly difficult.10

The combat air patrol’s Zeros attacked Henderson first. On their second pass, they sent him down in flames. The remaining SBDs continued the gliding attack. One by one, the Marines released their bombs��and missed. Some came petrifyingly close for the Hiryū’s crew, and many Marines mistakenly believed they had scored hits.11

Norris and his Vindicators arrived at about 0820, less than ten minutes after the surviving SBD-2s had departed and amid an attack by Army Air Forces B-17 Flying Fortresses. The combat air patrol had doubled to 26 fighters. Norris descended through the clouds toward the carrier Akagi. The Zeros could not find the dive bombers as long as they were in the safety of the cloud bank, but neither could the Marines see the ships below. When they emerged at 2,000 feet, they saw only the battleship Haruna. Norris also attempted a gliding attack. The Haruna maneuvered evasively, neatly avoiding every one of the Marines’ bombs. The SB2Us hugged the surface and flew back to Midway.12 Only 8 of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 8 of its 12 SB2U-3s returned.13

VMSB-241 conducted two more strikes during the battle. That evening Norris led five SB2U-3s and six SBD-2s in a vain search for burning carriers. They found nothing, and Norris did not return, lost in the inky, moonless squalls. On 5 June, VMSB-241 attacked the cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. The squadron lost another Vindicator to antiaircraft fire and again scored no hits.14

What Was Done Well

MAG-22 did some things remarkably well in its first action. Due to superb intelligence and early warning, no airworthy planes were caught on the ground. The fighter direction center placed the fighters in an optimum intercept position. The dive bombers located the Japanese carriers. Most impressively, every fighter and dive-bomber pilot attacked without hesitation into the teeth of a formidable defense.

MAG-22’s efforts indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Akagi and two other carriers, the Kaga and Sōryū, later that morning. As historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrated, the cumulative effect of the series of failed attacks by bombers from Midway and U.S. carriers created conditions that delayed Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s counterattack and placed his carriers at greater vulnerability to the dive bombers from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5). Dodging the attacks required the carriers to maneuver violently. Defending against them required the carriers to launch and recover fighters. Perhaps just as important, Nagumo faced a series of menacing dilemmas, complicating his decision-making. When the dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown appeared overhead at 1020, Kates and Vals were still below on the hangar decks, where their fuel and ordnance amplified the destructive power of the American bombs.15

VMF-221 also helped reduce the strength of Nagumo’s counterpunch when it did come. The only carrier that survived the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bomber attacks was the Hiryū. It was her air group that VMF-221 had attacked. Though the Marine fighters shot down just two Kates outright, another seven Kates were shot down by Marine antiaircraft guns, ditched, or were too damaged to participate in the strikes against the U.S. carriers.16 In other words, the Marines did not bring down many aircraft, but the ones they did bring down were the right ones—aircraft from the Hiryū’s air group.

Nonetheless, 4 June had been an awful day for MAG-22. It had lost many aircraft, shot down only a handful of the enemy, and hit no ships. Forty-two MAG-22 Marines had died; 36 pilots and gunners were missing; and six Marines had been killed in the bombing of Eastern Island.17

‘Not a Combat Airplane’

On 17 April, Major (soon to be Lieutenant Colonel) Ira L. Kimes (below) landed at Midway Atoll to replace Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace as MAG-22 commander. Accompanying Kimes were six second lieutenants, green aviators who replaced six captains, seasoned fliers, who left the atoll with Wallace three days later. Public Domain

Every surviving Marine fighter pilot from VMF-221 attested to the superiority of the Zero over the Marine fighters. Captain

The F2A-3 is not a combat airplane. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.

It is my belief that any commander that orders pilots out for combat in a F2A-3 should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.18

Kimes agreed. In his endorsement to his aviator’s statements, Kimes recommended that the fleet relegate the F2A-3 Buffalo, the F4F-3 Wildcat, and the SB2U-3 Vindicator to training commands.19

The Vindicator was indeed past its usefulness. However, there is evidence that neither fighter was to blame for VMF-221’s poor performance. With improved tactics, Marine and Navy pilots would achieve far better results with the F4F in the Solomons. Captain Marion Carl, the only Marine to shoot down a Zero over Midway, believed the F2A-3 was as maneuverable and fast as the F4F-3, and its only drawbacks were that it could not absorb punishment and was less stable as a gunnery platform than the Wildcat.20

Some British and Dutch Buffalo aces, whose squadrons suffered grievously against Imperial Japanese Navy Zeros, attributed their lopsided outcome to Japanese proficiency and numbers rather than the Buffalo’s inferiority. Finnish Buffalo pilots enjoyed great success flying the planes against the Soviets.21 The Buffalo’s mixed performance in other theaters suggests that other factors contributed to VMF-221’s poor performance.

‘Half-Baked Flyers’

When VMF-221 and VMSB-241 had landed on Eastern Island in December 1941, both squadrons were top heavy with experience. VMF-221’s most junior pilot had been flying for at least a year since flight school.22 But the 57 aviators who flew on 4 June included 35 second lieutenants, none of whom had been with their squadron more than four months, and 17 of whom had arrived on 27 May directly from flight school.23

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles.

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In the first half of 1942, Marine aviation had two conflicting missions: defending the fleet’s advanced bases and training new aviators. Newly winged aviators reported to the fleet with just 200 hours of flight time, and none in the aircraft they would fly in combat.24 The new aviators needed operational training, but the aircraft they needed to train in were defending advanced bases in the Pacific.

On 8 January 1942, Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell, the commander of 2d Marine Air Wing, described the dilemma in a letter to Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of Aircraft, Battle Force, Pacific Fleet: “I have now accumulated 35 second lieutenants in various stages of advanced training. . . . If ComAirBatFor approves and you want some half-baked flyers, send me a dispatch to that effect.” Halsey approved; he directed Rowell to order the green fliers to squadrons like VMF-221 and VMSB-241.25 This decision set in motion a sequence of personnel transfers that diluted the combat readiness of forward-deployed squadrons. As inexperienced aviators joined squadrons at advanced bases, experienced aviators left to form new squadrons in Hawaii and California.

Marine aviation was still following its prewar training pipeline. Once students were designated naval aviators, they reported to squadrons in the Fleet Marine Force for about a year of operational flight training in combat aircraft.26

Not only did MAG-22 not have a year to train its new aviators, but the group’s commitment to the defense of Midway also required it to devote most of its operational flights to patrols and radar calibration vice gunnery and tactics. Less than 30 percent of VMF-221’s missions from December 1941 to May 1942 were dedicated to improving the lethality of its fighter pilots.27

Logistics shortfalls further impinged on the group’s training. A shortage of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition often limited gunnery practice to dummy runs.28 In the final week before combat, PBY Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortresses drew thirstily from Midway’s fuel stocks, which were already limited due to an incredible blunder. On 22 May, demolition charges placed at an underground fuel storage facility detonated when one of the defense battalion batteries fired its 11-inch guns. The station lost 375,000 gallons of precious aviation fuel and its pipeline to Eastern Island.29 The resulting shortage prevented the group from providing the 17 Marines fresh out of flight school with anything more than familiarization flights. VMSB-241 could not even check out its new pilots in their SBDs.30

Without question, MAG-22 fought the Battle of Midway with inferior aircraft and many “half-baked” pilots. Though the odds were stacked against the group’s aviators, command decisions may have stacked the odds higher than they needed to be.

‘No Organized Plan Whatsoever’

In a 1966 interview, MAG-22’s former executive officer stated there had been “no organized plan whatsoever” to coordinate Midway’s Army Air Forces, Navy, and Marine aircraft.31 Though not strictly true, his characterization betrays how Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 struggled to coordinate air operations.

In anticipation of the coming fight, Nimitz had abundantly reinforced Midway. In addition to MAG-22, Midway’s air force included 31 PBYs, 17 B-17s, the 4 B-26s, and the 6 TBFs. Nimitz assigned tactical control of all these to the naval air station commander, Navy Captain Cyril T. Simard, and sent an experienced aviator and a naval base air defense detachment to coordinate air operations.32

While the naval air station directed scouting operations superbly, integrating the bombers in a coordinated strike proved beyond its reach. Each aircraft type attacked without regard to the next, permitting the Japanese the opportunity to fend off each in turn. As Kimes observed in perfect hindsight, “It would have been better had they arrived simultaneously.”33

Coordination was exacerbated by the physical separation of the naval air station and MAG-22 command posts. Simard and his air operations officer were on Sand Island; Kimes and his command post were on Eastern Island. According to Kimes’ executive officer, the “Marines ran their own show” but did not command the other services’ bombers on Eastern Island, including the six Navy TBFs.34

Kimes’ air group struggled to coordinate its own aircraft. VMSB-241 does not seem to have attempted to integrate its SBD and SB2U attacks. Most puzzlingly, MAG-22 allocated no fighter protection to VMSB-241 for its strike against the Japanese carriers.

‘Go All Out for the Carriers’

Kimes employed his fighting squadron in what Marine Corps doctrine termed “general support.” As then–Major William J. Wallace lectured Marine officers at Quantico in 1941, general support was an offensive mission that allowed fighters the freedom to be “on the prowl.” In contrast, missions that tied fighters to protection missions, such as escorting bombers, were termed “special support.” As a fighter pilot, Wallace clearly favored the freedom to go find trouble and emphasized, “The rule, then, for the employment of fighter units should be-—general support wherever and whenever possible.”35

In January 1942, now–Lieutenant Colonel Wallace took command of Marine aviation on Midway, which he retained until relieved by Kimes in April. It was Wallace who had developed the fighter direction system MAG-22 employed for defense of the atoll. As Wallace’s views on fighter employment reflected Marine Corps doctrine, and Wallace commanded MAG-22 until two months before the battle, this bias likely influenced Kimes’ decision to place all of VMF-221 in general support on 4 June.

MAG-22’s fighter employment stands in stark contrast to how Japanese and U.S. carrier task forces operated on 4 June. Carriers were far more vulnerable to air attack than an island base. Nonetheless, every Japanese and American task force commander allocated fighter escorts to increase their bombers’ chances of getting through the enemy’s fighters.

Hitting the Japanese fleet was exactly what Nimitz had in mind when he reinforced Midway with so many aircraft. On 20 May, Nimitz provided the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, with some views on the role of land-based aircraft he had drawn from the recent Battle of the Coral Sea:

The shore commander should assign attack missions designed to render the greatest possible assistance to the Fleet Task Force when it is engaged and should particularly be ready to provide fighter protection when it is practicable.36

Nimitz incorporated these views in his planning guidance for Midway. In a 23 May memorandum to his chief of staff, Captain Milo F. Draemel, Nimitz explicitly directed that “Midway planes must thus make the CV’s [aircraft carriers] their objective, rather than attempting any local defense of the atoll.”37 In an undated memorandum likely written about the same time, Nimitz reiterated his intent to Captain Arthur C. Davis, his air officer:

Balsa’s [Midway’s] air force must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks if recurring attacks are to be stopped. Our objectives will be first—their flight decks rather than attempting to fight off the initial attacks on Balsa. . . . If this is correct, Balsa air force . . . should go all out for the carriers . . . leaving to Balsa’s guns the first defense of the field.38

But in his operations order for Midway, Nimitz was less clear in the tasks he assigned to Simard at Midway:

(1) Hold MIDWAY.

(2) Aircraft obtain and report early information of enemy advance by searches to maximum practicable radius from MIDWAY covering daily the greatest arc possible with the number of planes available between true bearings from MIDWAY clockwise two hundred degrees dash twenty degrees. Inflict maximum damage on enemy, particularly carriers, battleships, and transports.

(3) Take every precaution against being destroyed on the ground or water. Long range aircraft retire to OAHU when necessary to avoid such destruction. Patrol planes fuel from AVD [seaplane tender] at French Frigate Shoals if necessary.

(4) Patrol craft patrol approaches; exploit favorable opportunities to attack carriers, battleships, transports, and auxiliaries. Observe KURE and PEARL and HERMES REEF. Give prompt warning of approaching enemy forces.

(5) Keep Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander Hawaiian Sea Frontier fully informed of air searches and other air operations; also the weather encountered by search planes.39

The very explicit language Nimitz used in his planning guidance—that Midway’s aircraft “should go all out for the carriers”—is not reflected in his order. Absent such direction, Simard left it to Kimes to command the Marine squadrons as he saw fit. In accordance with Marine Corps doctrine, Kimes placed his fighting squadron in general support over Midway—and sent his dive bombers against the Japanese fleet without fighter escorts. Had he allocated one or two divisions from VMF-221 to escort VMSB-241, more Marine dive bombers may have survived to drop bombs on the Hiryū, and their accuracy may have improved had they attacked with less interference from the Japanese combat air patrol.

Trying to Do More with Less

MAG-22 had not gone all out for the carriers but had massed its fighters in defense of Midway. Naval Air Station Midway had struck the Japanese carriers with every bomber available but had been unable to coordinate their attacks to increase their chances for success and survival. Most tragically, many of the Marines lost in the battle were just not ready to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy, despite their willingness and eagerness to try.

MAG-22’s very bad day is a cautionary tale. Trying to do more with less—in MAG-22’s case, trying to defend Midway while training novice aviators—carries risks that may be hidden until they are exposed through combat. In his report of the battle, Kimes included a page and a half of candid comments and recommendations.40 After Midway, Marine aviators applied the lessons MAG-22 had learned at enormous cost and achieved spectacular results against the same foe in the Solomons, often under the leadership of aviators who had survived Midway.

Those same lessons are noteworthy today. Naval experts have cautioned the naval services against maintaining too much forward presence with too little fleet.41 An enduring lesson of MAG-22 may be that very bad days result from very bad choices, and that choosing to do more with less is often a very bad choice.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 2.4 (before 1940)

62 – Earthquake in Pompeii, Italy. 1576 – Henry of Navarre abjures Catholicism at Tours and rejoins the Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion. 1597 – A group of early Japanese Christians are killed by the new government of Japan for being seen as a threat to Japanese society. 1783 – In Calabria, a sequence of strong earthquakes begins. 1810 – Peninsular War: Siege of Cádiz begins. 1818 – Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte ascends to the thrones of Sweden and Norway. 1852 – The New Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, one of the largest and oldest museums in the world, opens to the public. 1859 – Alexandru Ioan Cuza, Prince of Moldavia, is also elected as prince of Wallachia, joining the two principalities as a personal union called the United Principalities, an autonomous region within the Ottoman Empire, which ushered in the birth of the modern Romanian state. 1862 – Moldavia and Wallachia formally unite to create the Romanian United Principalities. 1869 – The largest alluvial gold nugget in history, called the "Welcome Stranger", is found in Moliagul, Victoria, Australia. 1885 – King Leopold II of Belgium establishes the Congo as a personal possession. 1901 – J. P. Morgan incorporates U.S. Steel in the state of New Jersey, although the company would not start doing business until February 25 and the assets of Andrew Carnegie's Carnegie Steel Company, Elbert H. Gary's Federal Steel Company, and William Henry Moore's National Steel Company were not acquired until April 1. 1905 – In Mexico, the General Hospital of Mexico is inaugurated, started with four basic specialties. 1907 – Belgian chemist Leo Baekeland announces the creation of Bakelite, the world's first synthetic plastic. 1913 – Greek military aviators, Michael Moutoussis and Aristeidis Moraitinis perform the first naval air mission in history, with a Farman MF.7 hydroplane. 1913 – Claudio Monteverdi's last opera L'incoronazione di Poppea was performed theatrically for the first time in more than 250 years. 1917 – The current constitution of Mexico is adopted, establishing a federal republic with powers separated into independent executive, legislative, and judicial branches. 1917 – The Congress of the United States passes the Immigration Act of 1917 over President Woodrow Wilson's veto. 1918 – Stephen W. Thompson shoots down a German airplane; this is the first aerial victory by the U.S. military. 1918 – SS Tuscania is torpedoed off the coast of Ireland; it is the first ship carrying American troops to Europe to be torpedoed and sunk. 1919 – Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith launch United Artists. 1924 – The Royal Greenwich Observatory begins broadcasting the hourly time signals known as the Greenwich Time Signal. 1933 – Mutiny on Royal Netherlands Navy warship HNLMS De Zeven Provinciën off the coast of Sumatra, Dutch East Indies. 1939 – Generalísimo Francisco Franco becomes the 68th "Caudillo de España", or Leader of Spain.

0 notes

Photo

NAVY BIRTHDAY

On October 13th, the United States Navy observes its birthday every year.

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is currently the largest, most powerful navy in the world, with the highest combined battle fleet tonnage. The service has over 340,000 personnel on active duty and more than 71,000 in the Navy Reserve.

With only two ships and a crew of eighty men, the Continental Army was born on October 13, 1775. The decision of the Continental Congress set the Continental Navy on course to carry arms to the British army, not to defend against it. However, these two ships and crew represent the birth of the United States Navy.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, their importance grew. Today, the United States maintains 40 naval bases across the country, including the world’s largest Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia.

Below the sea, submarines became a part of the Navy during World War II. While experiments began in the late 1800s and during the Civil War, they did not become a large part of the Navy inventory until World War II. At that point, subs became necessary for surveillance and rescue, even though they were also armed.

With the advent of the airplane, the Navy became vital stations for the Airforce as well. As a result, the Navy modified ships into floating landing strips. Today, joint Naval and Airbases such as Pearl Harbor-Hickam provided necessary fleets of sea and air defense.

NAVY BIRTHDAY HISTORY

On October 13, 1775, the Continental Congress authorized the first American naval force. Thus began the long and prestigious heritage of the United States Navy. Between 1922 and 1972, the Navy celebrated its birthday on October 27th, the date of Theodore Roosevelt’s birth. The Navy League of the United States designated the date due to Roosevelt’s foresight and vision in elevating the U.S. Navy into a premier force. Regardless of when the Navy observed its birth, the celebration has always been one of pride.

The change to October 13 was seen as a more relevant date in line with the first official action legislating a navy. Since 1972, the Navy has officially recognized October 13th as the official date of its birth.

Source

The United States’ Continental Congress ordered the establishment of the Continental Navy (later renamed the United States Navy) on October 13, 1775.

#US Navy's Birthday#Continental Navy#United States Navy#13 October 1775#TheUsNavysBirthday#245th anniversary#US history#USA#Texas#ship#USS LEXINGTON Aircraft Carrier Museum-Corpus Christi#summer 2011#2010#original photography#Gulf of Mexico#beach#National Naval Aviation Museum#Pensacola#A-4E Skyhawk#Blue Angels#Naval Aviator Monument#F-14A Tomcat#F-8A Crusader#Flight Deck

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

130361 1955 Douglas YEA-3A Skywarrier US Navy Pima Air & Space Museum 25.06.99 by Phil Rawlings Via Flickr: Constructed as an A3D-1 and brought on charge with the USN 31.03.55. Transferred to El Segundo and 30.04.55 to O & R Norfolk. 05.07.55 converted to A3D-1Q. 16.01.56 transferred to NATC LANT, Pax River. 13.04.56 transferred to O & R Norfolk. 06.09.56 transferred to VQ-2, Port Lyautey. 21.03.60 transferred to NATC, RDT and E, Pax River. 1962 redesignated as YEA-3A. 09.04.63 converted to an EA-3A. 10.04.63 taken on Strength/Charge with the United States Army with serial 130361. 25.01.64 transferred to BWR FR, Baltimore. 25.01.64 struck off Strength/Charge from the United States Army. 2.03.69 taken on Strength/Charge with the United States Navy with serial 130361. 27.03.69 transferred to Naval Air Testing Center, Patuxent River NAS. 08.09.69 transferred to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center (MASDC) with inventory number 2A0039. 31.12.70 struck off Charge from the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center MASDC) and to the National Naval Aviation Museum, NAS Pensacola, Pensacola, FL. Loaned to Pima Air and Space Museum, Davis-Monthan AFB (South Side), Tucson, AZ in 1980. Restored c1996 and markings Applied: W, NAVY, 130361, W finished in the markings of the Naval Air Testing Center, Patuxent River NAS, from 1969.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saudi Muslim kills 3, wounds 8 in shooting at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida

Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani was shot dead but not before killing 3 and wounding 8 others.

PENSACOLA, Fla. — A Saudi man training at the Naval Air Station Pensacola opened fire on the base early Friday morning with a handgun, killing three and injuring eight before deputies fatally shot him, authorities said.

President Donald Trump, who spoke with King Salman of Saudi Arabia shortly after the shooting, said the monarch called the attack "barbaric."

The shooter was identified as Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani, a member of the Saudi military, a U.S. Defense official told USA TODAY. The official wasn’t authorized to discuss the matter publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity. A motive for the attack is unknown.

Alshamrani was one of 852 Saudi nationals in the United States training under the Pentagon’s security cooperation agreement with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, according the Defense official. Alshamrani, began his three-year course in August 2017 with English, basic aviation and initial pilot training.

The shooting began around 6:30 a.m. CT and the suspect was halted by two Escambia County sheriff's deputies, who arrived on scene in less than five minutes, Sheriff David Morgan said. One of the deputies fatally shot the gunman, he said.

An official who was not authorized to speak publicly told USA TODAY that the Saudi national did not use his military-issued service weapon.

One of the officers was shot in arm and treated at a local hospital. The other was shot in the knee and was undergoing surgery. Authorities expected both to survive. The shooting happened on two floors of the building.

"The best of our community was on scene today and that's why it turned out the way it did," Morgan said of the deputies who responded. "They ran to the fight, not from the fight."

Morgan said his deputies train regularly with base personnel for the type of attack that they encountered.

Defense Secretary Mark Esper said he and others are watching the situation closely.

"I've spoken with the Secretary of the Navy, and Deputy Secretary (David) Norquist and am considering several steps to ensure the security of our military installations and the safety of our service members and their families," Esper said. "I'm grateful for the heroism of the first responders and law enforcement who helped confront both situations and kept further loss of life from occurring."

The FBI has taken the lead in the investigation, though there has been no immediate determination on whether the shooting was terror related, two sources told USA TODAY.

The shooting was the second in a week at a U.S. Navy base.

Navy Adm. Mike Gilday, chief of naval operations, said it has been "a devastating week for our Navy family."

"Our hearts break for those who lost their lives in Pensacola and the wrenching pain it causes their loved ones," he said. "When tragedy hits, as it did today, and Wednesday in Pearl Harbor, it is felt by all."

Like most military installations, personal firearms are not normally permitted on the base, which provides a wide variety of training to both U.S. and international aviators, dating back to the British Royal Air Force during WWII.

The Pensacola base is also home of the Blue Angels, the Navy's Flight Demonstration Squadron, and the National Naval Aviation Museum. Located in the far western Panhandle, the base employs more than 16,000 military and 7,400 civilian personnel.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Navy veteran, asked all Americans to remember the dead and wounded, along with their families: "They need your prayers and they need your comfort."

Eight patients, including the deputies, were taken to nearby Baptist Hospital. One of the victims died at the hospital, and two died on the base. The shooter also died on the base. The names of the victims will not be released until the next of kin have been notified, authorities said.

"Walking through the crime scene was like being on the set of a movie," Morgan said. "This doesn't happen in Escambia County. This doesn’t happen in Pensacola . . . So now we’re here to pick up the pieces."

The shooter was in aviation training at the base, along with "several hundred" other international airmen, authorities said. DeSantis said the shooter's nationality will complicate the investigation.

"Obviously, the government of Saudi Arabia needs to make things better for these victims," DeSantis said in a press conference. "They’re going to owe a debt here."

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Is it not past time to end training foreign Muslims on U.S. soil at taxpayer expense? Is this an America First policy?

via In the 2018 fiscal year, the U.S. trained 1,753 Saudi military members at an estimated cost of $120,903,786, according to DoD records.

In the 2018 fiscal year, some 62,700 foreign military students from 155 countries participated in U.S.-run training, the total cost of which was approximately $776.3 million, according to DoD records.

Among them is a contingent Saudis who recently arrived at Naval Air Station Pensacola.

In recent weeks, 18 naval aviators and two aircrew members from the Royal Saudi Naval Forces were training with the U.S. Navy, including a stint at Pensacola, according to a November 15 press release from the Navy.

It was not clear if the suspected shooter was part of that delegation.

The delegation came under a Navy program that offers training to U.S. allies, known as the Naval Education and Training Security Assistance Field Activity.

A person familiar with the program said that Saudi Air Force officers selected for military training in the United States are intensely vetted by both countries.

The Saudi personnel are 'hand-picked' by their military and often come from elite families, the person said, speaking on condition of anonymity because they did not have permission to speak to a reporter. Trainees must speak excellent English, the person said.

Saudi Arabia's embassy in Washington did not respond to questions.

Saudi Arabia, a major purchaser of U.S. arms, accounts for a massive portion of America's spending on foreign military training.

In the 2018 fiscal year, the U.S. trained 1,753 Saudi military members at an estimated cost of $120,903,786, according to DoD records.

For fiscal year 2019, the State Department planned to train roughly 3,150 Saudis in the U.S.

---------------------------------------------

One Florida Senator has requested a review - but is it just reactionary posturing? via Twitter:

DEVELOPING: Sen. Rick Scott has called for a review of military programs for foreign nationals, saying he is "extremely concerned" about the military training foreign nationals following today's shooting that left four people dead at Pensacola Naval Air Base in Florida - The Hill

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WC54 ambulances lining up on a pier to take wounded off USS Intrepid, probably Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, 1944-1945

United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tourist Guide to Pensacola, Florida

Situated in northwest Florida, ten miles from the Alabama state line on its beg, Pensacola is wealthy in notable, military aeronautics, and characteristic sights, all with Florida's unique sun, sand, fish, and water perspectives Wedding Bands Pensacola:

Despite the fact that St. Augustine, on Florida's east or Atlantic coast, is viewed as the most seasoned US city and flourished after Admiral Pedro Menendez de Aviles cruised to it and set up a province, Pensacola, on the state's west or Gulf of Mexico side, might have guaranteed the title if its own settlement had endured.

Six years sooner, in August of 1559, Spanish wayfarer Tristan de Luna moored in a zone nearby clans named "Panzacola," for "long-haired individuals," with the aim of completing Luis de Velasco, the Mexican emissary of Spain's request for building up a settlement on the sound.

Very much provisioned and arranged, he was furnished with 11 ships and brought 1,500 would-be pilgrims, among whom were African slaves and Mexican Indians. Be that as it may, history had to take some unacceptable byway when a savage storm wrecked eight of de Luna's vessels on September 19.

By the by, with an end goal to rescue the endeavor, he sent one of them to Veracruz, Mexico, to inspire help, leaving the outsiders to squeeze out a presence on shore and make due by depleting the provisions they had brought. However, rather than re-provisioning the homesteaders, the boats, showing up a year later, just saved the survivors by taking them to Havana and leaving minimal in excess of a military station by the spring of 1561. By August, the modest bunch of warriors relinquished the new land site and got back to Mexico, esteeming it excessively perilous for settlement.

In spite of the fact that it was past information at that point, a specialty as the most seasoned, ceaseless US city it could always be unable to make.

It would be very nearly 150 years, in 1698, indeed, that unfamiliar powers would by and by try to increase a traction for this situation, Spain set up a more effective post in what might become cutting edge Pensacola and toward that end spread out a provincial town.

As has so regularly happened since the beginning, land, once guaranteed, turned into the prize others looked for, frequently by military methods, and Pensacola demonstrated no exemption. Spaniards at first gave up to the French in May of 1719, however it was not really the finish of its possession. France, Spain, Britain, and Spain indeed would take ownership throughout the following century, until the last at last surrendered Florida to the United States in 1821. Since the Confederacy additionally "took up residency," Pensacola is considered the "City of Five Flags."

A noteworthy bit of its right around 500-year history has been safeguarded and can be knowledgeable about the Pensacola Historic District, which is overseen by the UWF Historic Trust, itself an association upheld by the University of West Florida, and it comprises of 27 properties on the National Register of Historic Places.

Affirmation, just available for seven days, incorporates guided visits and guest section, and tickets can be gotten at Tivoli High House.

Significant structures are many. Seville Square, for instance, is the focal point of the old settlement and filled in as one finish of the British course's motorcade ground, finishing at its twin, Plaza Ferdinand VII. It was here that General Andrew Jackson acknowledged the West Florida domain from Spain in 1821 and first raised the US banner.

A little, protected segment of Fort George, an objective of the American Revolution's Battle of Pensacola, is emblematic of British occupation from 1763 to 1781.

Unique houses proliferate, including the Julee Panton Cottage, the 1805 Lavalle House, the 1871 Dorr House, and the 1890 Lear-Rocheblave House.

The Old Christ Church, situated on Seville Square and inherent 1824 by slave work, is the most seasoned of its sort in the state to at present possess its unique site.

There are likewise a few exhibition halls: the T.T. Wentworth, Jr., Florida State Museum, which was developed in 1908 and initially filled in as the City Hall, the Pensacola Children's Museum, the Voices of Pensacola Multicultural Center, and the Museum of Commerce.

Despite the fact that not actually part of the Pensacola Historic District, the Pensacola Grand Hotel is situated on the site of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad's traveler stop, which itself was developed in 1912 to supplant the first 1882 L&N Union Station that served Pensacola for a very long time. It is currently on the National Register of Historic Places.

Reestablished in its unique wonder and changed into a lodging with a 15-story glass tower, it holds quite a bit of its initial embellishment, including a French earth tile rooftop and a clay mosaic tile floor, and is decorated with period pieces, for example, a strong, drop-cast bronze light and classical goods.

Its lavish "1912, The Restaurant," situated on the ground floor, highlights gateway Biva entryways from London, a cast-bronze French-style light fixture from Philadelphia, 1885 angled glass from a Victorian lodging in Scranton, and scalloped-molded flame broil work from Lloyd's of London.

Maritime Air Station Pensacola:

There are a few huge attractions on Naval Air Station Pensacola, which can be gotten to by the guest's entryway and requires ID, for example, a permit, to enter

Found itself on the site of a Navy yard that was raised in 1825, it started as an avionics preparing station at the flare-up of World War I with nine officials, 23 mechanics, eight planes, and ten sea shore propped tents, and was viewed as the first of its sort.

Drastically growing due to the Second World War, it prepared 1,100 cadets for every month, who aggregately flew nearly 2,000,000 hours. After its Naval Air Basic Training Command moved its base camp from Corpus Christi, Texas, to Pensacola, unadulterated fly airplane were consolidated in the prospectus. Today, 12,000 dynamic military work force, 9,000 of whom get flying preparing, are doled out to the station.

The widely acclaimed National Naval Aviation Museum, likewise situated here, is the biggest and one of Florida's most-visited attractions. It started not as a vacationer sight, but rather as a methods for remembering maritime flying history for cadet educational plans, for which there was neither adequate time nor subsidizing for the customary book-and-study methodology.

The office, at first housed in a 8,500-square-foot wood outline constructing that hailed from World War II, turned into the locus of determination, assortment, conservation, and show of airplane and curios that speak to the turn of events and legacy of the administration branch. It opened its entryways on June 8, 1963.

Ever-growing, it presently has 700 planes in its assortment that are shown in its 11 other authority Navy galleries all through the nation, yet nearly 150 immaculately reestablished ones are as yet displayed here after another office with 37 outside sections of land and 350,000 square feet of indoor space was finished. Confirmation is free.

Partitioned into the South Wing, the West Wing, a second-floor Mezzanine, and the different Hangar Bay One, it follows the development of Navy flight and the airplane it worked from its beginning to the most recent Middle East clashes.

The A-1 Triad, for instance, was so named since, in such a case that worked in the three domains of air (wings), water (buoys), and land (wheels). The Nieuport 28, in the World War I segment, encouraged plane carrying warship experimentation, while the mammoth Navy-Curtiss NC-4, at the limit of the Golden Age display, was the first to navigate the Atlantic from Trepassey, Newfoundland, to the Azores Islands off of Portugal.

Speed from stream warriors during the Cold War is spoken to by such kinds as the McDonnell F2H-4 Banshee, the North American FJ-2 Fury, and the Russian MiG-15.

Highlight of the West Wing is the "USS Cabot" island and a copy of its transporter deck, which is encircled by a broad assortment of for the most part World War II airplane, including the Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat, the Vought-Sikorsky FG-1D Corsair, and the General Motors (Grumman) TBM Avenger.

Of the various shows on the exhibition hall's mezzanine, which itself disregards both the South and West Wings and can even be gotten to via aircraft ground steps, there can be none that offer a more prominent differentiation to one another than those gave to lighter-than-air avionics and space investigation.

Advanced from the round inflatable first effectively flown by the Montgolfier Brothers in 1783 in the main case, carriers were huge, controllable inflatables which achieved lift by the lightness standard themselves, yet fused motors for impetus and rudders and lifts for, individually, yaw (guiding) and longitudinal (pitch) hub control. Suspended gondolas housed the team and travelers. Inflexible sorts included inner systems, which were not needed by the non-unbending ones, for example, dirigibles.

Gondolas or control vehicles from the Navy's L-8 and World War II-period K-47 aircrafts are in plain view. The last mentioned, conveyed on May 19, 1943 at Moffett Field, California, had a 425,000-cubic-foot inner volume.

In the second, or space, case, a reproduction of the Mercury Freedom 7 space container, the first was dispatched at 116.5 nautical miles and was air/space borne for 14.8 minutes, speaks to Naval Aviation's commitments to the Space Program, on the grounds that Naval Aviator Alan B. Shepard turned into the primary American to enter that domain on May 5, 1961.

Likewise in plain view is the first Skylab II Command Module, which circled the Skylab space station during 28 days among May and June of 1973. Worked by a three-part, all-Navy team, it set a few precedents, including the longest monitored spaceflight, the best separation voyaged, and the best mass docked in space.

Noticeable from both the mezzanine and the fundamental floor is the 75-foot-tall, 10,000-square-foot Blue Angels Atrium that associates the South and West Wings and highlights four Douglas A-4 Skyhawks in a plunging precious stone painted in the aerobatic group's dim blue attire.

0 notes

Text

The True Story of the Battle of Midway

https://sciencespies.com/history/the-true-story-of-the-battle-of-midway/

The True Story of the Battle of Midway

“At the present time we have only enough water for two weeks. Please supply us immediately,” read the message sent by American sailors stationed at Midway, a tiny atoll located roughly halfway between North America and Asia, on May 20, 1942.

The plea for help, however, was a giant ruse; the base was not, in fact, low on supplies. When Tokyo Naval Intelligence intercepted the dispatch and relayed the news onward, reporting that the “AF” air unit was in dire need of fresh water, their American counterparts finally confirmed what they had long suspected: Midway and “AF,” cited by the Japanese as the target of a major upcoming military operation, were one and the same.

This codebreaking operation afforded the United States a crucial advantage at what would be the Battle of Midway, a multi-day naval and aerial engagement fought between June 3 and 7, 1942. Widely considered a turning point in World War II’s Pacific theater, Midway found the Imperial Japanese Navy’s offensive capabilities routed after six months of success against the Americans. As Frank Blazich, lead curator of military history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, explains, the battle leveled the playing field, giving U.S. forces “breathing room and time to go on the offensive” in campaigns such as Guadalcanal.

Midway, a new movie from director Roland Emmerich, known best for disaster spectacles like The Day After Tomorrow, traces the trajectory of the early Pacific campaign from the December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor to the Halsey-Doolittle Raid in April 1942, the Battle of the Coral Sea in May of that same year, and, finally, Midway itself.

Ed Skrein (left) and Luke Kleintank (right) play dive bombers Dick Best and Clarence Dickinson.

(Reiner Bajo/Lionsgate)

More

Traditional military lore suggests a Japanese victory at Midway would have left the U.S. West Coast vulnerable to invasion, freeing the imperial fleet to strike at will. The movie’s trailer outlines this concern in apt, albeit highly dramatic, terms. Shots of Japanese pilots and their would-be American victims flash across the screen as a voiceover declares, “If we lose, then [the] Japanese own the West Coast. Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles will burn.”

The alternative to this outcome, says Admiral Chester Nimitz, played by Woody Harrelson in the film, is simple: “We need to throw a punch so they know what it feels like to be hit.”

***

According to the National WWII Museum, Japan targeted Midway in hopes of destroying the U.S. Pacific Fleet and using the atoll as a base for future military operations in the region. (Formally annexed in 1867, Midway had long been a strategic asset for the United States, and in 1940, it became a naval air base.) Although the attack on Pearl Harbor had crippled the U.S. Navy, destroying three battleships, 18 assorted vessels and 118 aircraft, the Doolittle Raid—a bombing raid on the Japanese mainland—and the Battle of the Coral Sea—a four-day naval and aerial skirmish that left the Imperial Navy’s fleet weakened ahead of the upcoming clash at Midway—showed Japan the American carrier force was, in Blazich’s words, “still a potent threat.”

Cryptanalysts and linguists led by Commander Joseph Rochefort (played by Brennan Brown in the film) broke the Japanese Navy’s main operational code in March 1942, enabling the American intelligence unit—nicknamed Station Hypo—to track the enemy’s plans for an invasion of the still-unidentified “AF.” Rochefort was convinced “AF” stood for Midway, but his superiors in Washington disagreed. To prove his suspicions, Rochefort devised the “low supplies” ruse, confirming “AF”’s identity and spurring the Navy to take decisive counter-action.

youtube

More

More

Per the Naval History and Heritage Command, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Etsushi Toyokawa), commander of Japan’s imperial fleet, grounded his strategy in the assumption that an attack on Midway would force the U.S. to send reinforcements from Pearl Harbor, leaving the American fleet vulnerable to a joint strike by Japanese carrier and battleship forces lying in wait.

“If successful, the plan would effectively eliminate the Pacific Fleet for at least a year,” the NHHC notes, “and provide a forward outpost from which ample warning of any future threat by the United States would come.”

Midway, in other words, was a “magnet to draw the American forces out,” says Blazich.

Japan’s plan had several fatal flaws, chief among them the fact that the U.S. was fully aware of how the invasion was supposed to unfold. As Blazich explains, “Yamamoto does all his planning on intentions of what he believes the Americans will do rather than on our capabilities”—a risky strategy made all the more damaging by the intelligence breach. The Japanese were also under the impression that the U.S.S. Yorktown, an aircraft carrier damaged at Coral Sea, was out of commission; in truth, the ship was patched up and ready for battle after just two days at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard.

Blazich emphasizes the fact that Japan’s fleet was built for offense, not defense, likening their Navy to a “boxer with a glass jaw that can throw a punch but not take a blow.” He also points out that the country’s top military officers tended to follow “tried and true” tactics rather than study and learn from previous battles.

“The Japanese,” he says, “are kind of doomed from the start.”

***

The first military engagement of the Battle of Midway took place during the afternoon of June 3, when a group of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers launched an unsuccessful air attack on what a reconnaissance pilot had identified as the main Japanese fleet. The vessels—actually a separate invasion force targeting the nearby Aleutian Islands—escaped the encounter unscathed, and the actual fleet’s location remained hidden from the Americans until the following afternoon.

“Dauntless” dive bombers approach the burning Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma on June 6, 1942.

(National Archives)

More

The U.S.S. Yorktown was struck by Japanese torpedo bombers during a mid-afternoon attack on June 4.

(National Archives)

More

Ensign Leif Larsen and rear gunner John F. Gardener in their Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless bombers

(U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation)

More

In the early morning hours of June 4, Japan deployed 108 warplanes from four aircraft carriers in the vicinity: the Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu. Although the Japanese inflicted serious damage on both the responding American fighters and the U.S. base at Midway, the island’s airfield and runways remained in play. The Americans counterattacked with 41 torpedo bombers flown directly toward the four Japanese carriers.

“Those men went into this fight knowing that it was very likely they would never come home,” says Laura Lawfer Orr, a historian at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. “Their [Douglas TBD-1 Devastators] were obsolete. They had to fly incredibly slowly … [and] very close to the water. And they had torpedoes that, most of the time, did not work.”

In just minutes, Japanese ships and warplanes had shot down 35 of the 41 Devastators. As writer Tom Powers explains for the Capital Gazette, the torpedo bombers were “sitting ducks for fierce, incessant fire from shipboard batteries and the attacks of the swift, agile defending aircraft.” Despite sustaining such high losses, none of the Devastators scored a hit on the Japanese.

Ensign George Gay, a pilot in the U.S.S. Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron 8, was the sole survivor of his 30-man aircrew. According to an NHHC blog post written by Blazich in 2017, Gay (Brandon Sklenar) crash landed in the Pacific after a showdown with five Japanese fighters. “Wounded, alone and surrounded,” he endured 30 hours adrift before finally being rescued. Today, the khaki flying jacket Gay wore during his ordeal is on view in the American History Museum’s “Price of Freedom” exhibition.

Around the time of the Americans’ failed torpedo assault, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo—operating under the erroneous assumption that no U.S. carriers were in the vicinity—rearmed the Japanese air fleet, swapping the planes’ torpedoes for land bombs needed to attack the base at Midway a second time. But in the midst of rearmament, Nagumo received an alarming report: A scout plane had spotted American ships just east of the atoll.

The Japanese switched gears once again, readying torpedo bombers for an assault on the American naval units. In the ensuing confusion, sailors left unsecured ordnance, as well as fueled and armed aircraft, scattered across the four carriers’ decks.

Black smoke pours from the U.S.S. Yorktown on June 4, 1942.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

More

On the American side of the fray, 32 dive bombers stationed on the Enterprise and led by Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky (Luke Evans) pursued the Japanese fleet despite running perilously low on fuel. Dick Best (Ed Skrein), commander of Bombing Squadron 6, was among the pilots participating in the mission.

Unlike torpedo bombers, who had to fly low and slow without any guarantee of scoring a hit or even delivering a working bomb, dive bombers plummeted down from heights of 20,000 feet, flying at speeds of around 275 miles per hour before aiming their bombs directly at targets.

“Dive bombing was a death defying ride of terror,” says Orr in Battle of Midway: The True Story, a new Smithsonian Channel documentary premiering Monday, November 11 at 8 p.m. “It’s basically like a game of chicken that a pilot is playing with the ocean itself. … A huge ship is going to appear about the size of a ladybug on the tip of a shoe, so it’s tiny.”

The Enterprise bombers’ first wave of attack took out the Kaga and the Akagi, both of which exploded in flames from the excess ordnance and fuel onboard. Dive bombers with the Yorktown, meanwhile, struck the Soryu, leaving the Japanese fleet with just one carrier: the Hiryu.

Close to noon, dive bombers from the Hiryu retaliated, hitting the Yorktown with three separate strikes that damaged the carrier but did not disable it. Later in the afternoon, however, a pair of torpedoes hit the partially repaired Yorktown, and at 2:55 p.m., Captain Elliott Buckmaster ordered his crew to abandon ship.

Dusty Kleiss is seated second from the right in this photograph of the U.S.S. Enterprise’s Scouting Squadron Six.

(William T. Barr/U.S. Navy)

More

Around 3:30 p.m., American dive bombers tracked down the Hiryu and struck the vessel with at least four bombs. Rather than continuing strikes on the remainder of the Japanese fleet, Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance (Jake Weber) opted to pull back. In doing so, Blazich explains, “He preserves his own force while really destroying Japanese offensive capability.”

Over the next several days, U.S. troops continued their assault on the Japanese Navy, attacking ships including the Mikuma and Mogami cruisers and the Asashio and Arashio destroyers. By the time hostilities ended on June 7, the Japanese had lost 3,057 men, four carriers, one cruiser and hundreds of aircraft. The U.S., comparatively, lost 362 men, one carrier, one destroyer and 144 aircraft.

Best and Dusty Kleiss, a bomber from the Enterprise‘s Scouting Squadron Six, were the only pilots to score strikes on two different Japanese carriers at Midway. Kleiss—whose exploits are at the center of the Smithsonian Channel documentary—scored yet another hit on June 6, sinking the Japanese cruiser Mikuma and upping his total to three successful strikes.

In Midway‘s trailer, Admiral Chester Nimitz, played by Woody Harrelson, says, “We need to throw a punch so they know what it feels like to be hit.”

(Lionsgate)

More

George Gay, the downed torpedo bomber memorialized at the American History Museum, watched this decisive action from the water. He later recalled, “The carriers during the day resembled a very large oil-field fire. … Billowing big red flames belched out of this black smoke, … and I was sitting in the water hollering hooray, hooray.”

***

The U.S. victory significantly curbed Japan’s offensive capabilities, paving the way for American counteroffensive strikes like the Guadalcanal Campaign in August 1942—and shifting the tide of the war strictly in the Allies’ favor.

Still, Blazich says, Midway was far from a “miracle” win ensured by plucky pilots fighting against all odds. “Midway is a really decisive battle,” the historian adds, “… an incredible victory.

But the playing field was more level than most think: While historian Gordon W. Prange’s Miracle at Midway suggests the Americans’ naval forces were “inferior numerically to the Japanese,” Blazich argues that the combined number of American aircraft based on carriers and the atoll itself actually afforded the U.S. “a degree of numerical parity, if not slight superiority,” versus the divided ranks of the Imperial Japanese Navy. (Yamamoto, fearful of revealing the strength of his forces too early in the battle, had ordered his main fleet of battleships and cruisers to trail several hundred miles behind Nagumo’s carriers.)

Naval historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully’s Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway deconstructs central myths surrounding the battle, including notions of Japan’s peerless strategic superiority. Crucially, Parshall and Tully write, “The imperial fleet committed a series of irretrievable strategic and operational mistakes that seem almost inexplicable. In so doing, it doomed its matchless carrier force to premature ruin.”

George Gay’s khaki flying jacket is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

(NMNH)

More

Luck certainly played a part in the Americans’ victory, but as Orr says in an interview, attributing the win entirely to chance “doesn’t give agency to the people who fought” at Midway. The “training and perseverance” of U.S. pilots contributed significantly, she says, as did “individual initiative,” according to Blazich. Ultimately, the Americans’ intelligence coup, the intrinsic doctrinal and philosophical weaknesses of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and factors from spur-of-the-moment decision-making to circumstance and skill all contributed to the battle’s outcome.

Orr says she hopes Midway the movie reveals the “personal side” of the battle. “History is written from the top down,” she explains, “and so you see the stories of Admiral Nimitz, [Frank Jack] Fletcher and Spruance, but you don’t always see the stories of the men themselves, the pilots and the rear seat gunners who are doing the work.”

Take, for instance, aviation machinist mate Bruno Gaido, portrayed by hearththrob Nick Jonas: In February 1942, the rear gunner was promoted from third to first class after he singlehandedly saved the Enterprise from a Japanese bomber by jumping into a parked Dauntless dive bomber and aiming its machine gun at the enemy plane. During the Battle of Midway, Gaido served as a rear gunner in Scouting Squadron 6, working with pilot Frank O’Flaherty to attack the Japanese carriers. But the pair’s plane ran out of fuel, leaving Gaido and O’Flaherty stranded in the Pacific. Japanese troops later drowned both men after interrogating them for information on the U.S. fleet.

Blazich cherishes the fact that the museum has George Gay’s khaki flying jacket on display. He identifies it as one of his favorite artifacts in the collection, saying, “To the uninformed you ignore it, and to the informed, you almost venerate it [as] the amazing witness to history it is.”

#History

#11-2019 Science News#2019 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#Nature Science#Our Nature#planetary science#Science#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#History

0 notes

Text

Porte-avions USS Saratoga (CV-3) en cale sèche – 1928

©United States Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation - 1989.119.002

#WWII#ww2#avant-guerre#pre war#marine américaine#us navy#marine militaire#military navy#porte-avions#arircraft carrier#classe lexington#lexington-class#uss saratoga (cv-3)#uss saratoga#cv-3#1928

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recovery of Gemini III

After orbiting the Earth three times, for 4 hours, 52 minutes, and 31 seconds, the Capsule of Gemini 3 splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean. The spacecraft was greeted by United States Navy swimmers dropped in from two helicopters from Squadron HS-3, which was assigned to USS INTREPID (CV-11).

"Navy swimmers are shown attaching a flotation collar to the Gemini-Titan 3 (GT-3) spacecraft during recovery operations following the successful flight."

"A frogman is lowered to the Gemini 3 spacecraft from a Navy helicopter of squadron HS-3."

Shown here, Navy swimmers are attaching a flotation collar to the spacecraft during recovery operations.

Astronaut John W. Young, the pilot of the Gemini 3 flight, waits in a life raft to be picked up by a helicopter.

Astronauts Virgil I. Grissom (left) and John W. Young are shown aboard a helicopter after being retrieved.

"Astronauts John W. Young and Virgil I. Grissom are shown in bathrobes receiving a warm welcome on the recovery ship, INTREPID."

Later on, INTREPID pulls up alongside the capsule and hoists it out of the water with a large crane on board.

Recovery patch

Date: March 23, 1965

NARA: 6734375, 6734376, 84455

NASA ID: S65-19229, S65-18528, S65-22893, S65-18656, S65-18733, S65-19224

U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation: 1993.501.073.235, 1993.501.073.240

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command: 65-H-456, 65-H-565, 1110684,

Intrepid Museum Archive: P2018.81.06

source, source

#GT-3#GT-III#Gemini 3#Gemini III#SC3#Molly Brown#NASA#Gemini Program#Project Gemini#Gemini Titan#rocket#Titan II#Titan II GLV#Splashdown#Splash Down#Recovery#1965#Atlantic Ocean#USS INTREPID (CV-11)#USS INTREPID#Essex Class#Aircraft Carrier#Ship#United States Navy#US Navy#Navy#USN#March#video#my post

179 notes

·

View notes

Video

Douglas A-1H Skyraider of VA-152 in flight over Vietnam in 1966 (NNMA.1996.253.2810). by manhhai Via Flickr: A U.S. Navy Douglas A-1H Skyraider (BuNo 137512) of Attack Squadron 152 (VA-152) "Friendlies" in flight in 1966. VA-152 was assigned to Attack Carrier Air Wing 16 (CVW-16) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CVA-34) for a deployment to Vietnam from 26 May to 16 November 1966. The A-1H 137512 was later lost over Laos to ground fire (location 191700N 1030600E) on 4 July 1969 while in service with the 56th Special Operations Wing, U.S. Air Force. The pilot, Col. Patrick M. Fallon, Vice Commander, 56th SOW, ejected safely, but was later missing in action, presumed dead. U.S. Navy - U.S. Navy National Naval Aviation Museum photo NNMA.1996.253.2810 ---------------------- List of United States bomber aircraft en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_bomber_aircraft

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Delta Air Lines celebrated 20 years of the Delta “Dream Flight” on Tuesday, July 16. A chartered Delta airplane took 150 students to the National Naval Aviation museum in Pensacola. The students, who were chaperoned by pilots and other individuals in the aviation sphere, toured the museum and watched as the United States Navy Blue Angels performed. This flight is a tailored experience for teenagers interested in an aviation career. The students’ interests ranged from a curiosity in aviation to accomplished solo flight participants. (Alyssa Pointer/AJC.COM) https://ift.tt/2Lt1QcS

0 notes

Video

130361 1955 Douglas YEA-3A Skywarrier US Navy Pima Air & Space Museum 25.06.99 by Phil Rawlings Via Flickr: Constructed as an A3D-1 and brought on charge with the USN 31.03.55. Transferred to El Segundo and 30.04.55 to O & R Norfolk. 05.07.55 converted to A3D-1Q. 16.01.56 transferred to NATC LANT, Pax River. 13.04.56 transferred to O & R Norfolk. 06.09.56 transferred to VQ-2, Port Lyautey. 21.03.60 transferred to NATC, RDT and E, Pax River. 1962 redesignated as YEA-3A. 09.04.63 converted to an EA-3A. 10.04.63 taken on Strength/Charge with the United States Army with serial 130361. 25.01.64 transferred to BWR FR, Baltimore. 25.01.64 struck off Strength/Charge from the United States Army. 2.03.69 taken on Strength/Charge with the United States Navy with serial 130361. 27.03.69 transferred to Naval Air Testing Center, Patuxent River NAS. 08.09.69 transferred to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center (MASDC) with inventory number 2A0039. 31.12.70 struck off Charge from the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center MASDC) and to the National Naval Aviation Museum, NAS Pensacola, Pensacola, FL. Loaned to Pima Air and Space Museum, Davis-Monthan AFB (South Side), Tucson, AZ in 1980. Restored c1996 and markings Applied: W, NAVY, 130361, W finished in the markings of the Naval Air Testing Center, Patuxent River NAS, from 1969.

6 notes

·

View notes